Franchisor Successfully Fends Off Fraud Claims

bkurtz@lewitthackman.com

tgrinblat@lewitthackman.com

February 2014

Kurtz Law Group Joins Lewitt Hackman Franchise Practice Group

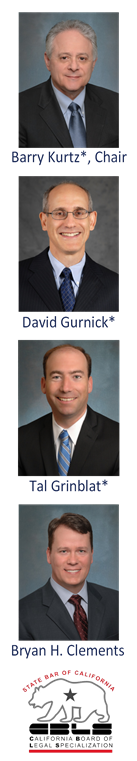

On February 1, 2014, the Kurtz Law Group joined Lewitt Hackman. Known for their “Focus on Franchise Law,” Barry Kurtz and his team have been one of the premier franchise law practices in California. Barry will chair the Franchise Practice Group, which now includes Barry, David Gurnick, Tal Grinblat, Candice Lee, Bryan Clements and two franchise law paralegals. Together, we have more than 85 years of experience representing franchisors, licensors, manufacturers, franchisees, licensees and distributors and are one of the largest, most experienced franchise law practice groups.

FRANCHISOR 101:

Franchisor Successfully Fends Off Fraud Claims

There are circumstances when a fraud claim will not succeed against a franchisor. In Dunkin’ Donuts Franchised Restaurants, LLC v. Claudia I, LLC, a franchisee alleged fraud by Dunkin’ Donuts, but a US District Court in Pennsylvania rejected its hardest hitting claims.

A Dunkin’ Donuts franchisee purchased a franchise and subleased a deteriorating store in Pennsylvania from Dunkin’. The franchisee’s owners believed they were paying above-market rent, and the sublease also overstated the size of the premises, so they believed they were overpaying common area expenses. The donut store lost money, the franchisee asked Dunkin’s consent to relocate, Dunkin’ declined and the franchisee stopped paying rent. The franchisor terminated both the franchise agreement and sublease and obtained an injunction requiring the franchisee to leave the store. Then, after retaking possession of the store, Dunkin’ moved the store to another location.

The franchisee claimed Dunkin misrepresented the store size and that it could renegotiate the sublease. The court ruled the franchisee could not prove fraud based on misrepresented square footage because the franchisee always suspected the stated square footage was wrong. Under the law, a person who believes a representation is false cannot claim to have relied on it and cannot prevail in a claim of fraud.

The court also found that any statement by Dunkin’ that the sublease could be renegotiated was also not actionable. A statement about what may happen in the future is not considered false, unless the speaker knowingly misstates his true state of mind. The court said renegotiation was a promise to do something in the future and noted that Dunkin’ actually had offered the franchisee a new, more favorable sublease. Therefore any pre-agreement representations could not have been knowingly false.

The court ruled, however, that the franchisee might be able to show Dunkin breached an implied contractual duty to act in good faith and in a commercially reasonable manner since Dunkin’ executives considered the store location to be bad, but had, nevertheless, sold the franchise and subleased the store to the franchisee and then, after taking back the store, relocated it itself, suggesting bad faith.

This case is a reminder to franchisors that appearances count. Here, refusing to consent to relocation, but then relocating a store after terminating the franchisee, gave the appearance of misconduct and was enough for the court to allow the franchisee’s breach of contract claim to proceed. For franchisees, the case is a reminder that you cannot claim reliance and recover for fraud if you had doubts or were suspicious about what the franchisor told you, or if the claimed fraud was a franchisor’s promise to do something in the future. To see the case, click Dunkin’ Donuts v. Claudia I, LLC.

FRANCHISEE 101:

Brewer’s Subsidiary Could Terminate Distributor

In 2008, Heineken made an acquisition that included the Strongbow Hard Cider brand. Esber Beverage Company, founded in 1937, is one of the oldest, family-owned beverage wholesalers in Ohio, as well as the United States, and distributed Strongbow in Ohio. Until 2013, Strongbow was imported into the USA by an independent company, VHCC. In 2013 Heineken terminated VHCC and entered into an agreement with its own subsidiary, Heineken USA (HUSA), naming the subsidiary as its exclusive U.S. import agent for Strongbow Hard Cider.

In 2008, Heineken made an acquisition that included the Strongbow Hard Cider brand. Esber Beverage Company, founded in 1937, is one of the oldest, family-owned beverage wholesalers in Ohio, as well as the United States, and distributed Strongbow in Ohio. Until 2013, Strongbow was imported into the USA by an independent company, VHCC. In 2013 Heineken terminated VHCC and entered into an agreement with its own subsidiary, Heineken USA (HUSA), naming the subsidiary as its exclusive U.S. import agent for Strongbow Hard Cider.

Under Ohio law, when ownership of an alcoholic beverage brand changes, a new manufacturer is permitted to terminate any distributor without cause upon notice within 90 days of the acquisition, allowing the manufacturer to assemble its own team of distributors. The notice triggers a valuation of the franchise and the new manufacturer must compensate the terminated franchisee for the reduced value of the business that is related to the sale of the terminated brand, including the value of the assets used in selling the brand and the goodwill of the brand.

Heineken and HUSA terminated Esber and, after a trial court in Ohio ruled that only a new owner could terminate the franchise and that Heineken USA was not a new owner, Heineken appealed. In Heineken USA, Inc. v. Esber Beverage Co., the appellate court ruled that Heineken USA was a successor that could terminate the distributor.

The court found that following the 2008 acquisition, Strongbow was imported into the USA by VHCC and VHCC supplied the Strongbow product to U.S. distributors, such as Esber. Heineken never owned any interest in VHCC. After Heineken terminated VHCC (and compensated VHCC as discussed above), Heineken no longer had an importer to supply Strongbow to U.S. distributors. It subsequently named HUSA as supplier of Strongbow, starting in January 2013. The appellate court ruled that VHCC had been the U.S. supplier of Strongbow, and VHCC, not Heineken, entered into contractual relationships with distributors, such as Esber. Once Heineken lawfully terminated its agreement with VHCC, Heineken acquired the right to decide who would import and supply Strongbow to distributors.

This decision indicates that in some states brewers may have additional flexibility to determine who will distribute their products domestically following an importer’s acquisition of the brands. To see the case, click Heineken v. Esber.